HULL, ENGLAND

December 28, 2018

STRANGER: Bernie Clifton

LOCATION: Snobs Bar, The Kingston Theatre Hotel, 1-2 Kingston Square, Hull, England

THEME: Getting coffee with a legendary British comedian and singer

Bernie Clifton is near the finishing line.

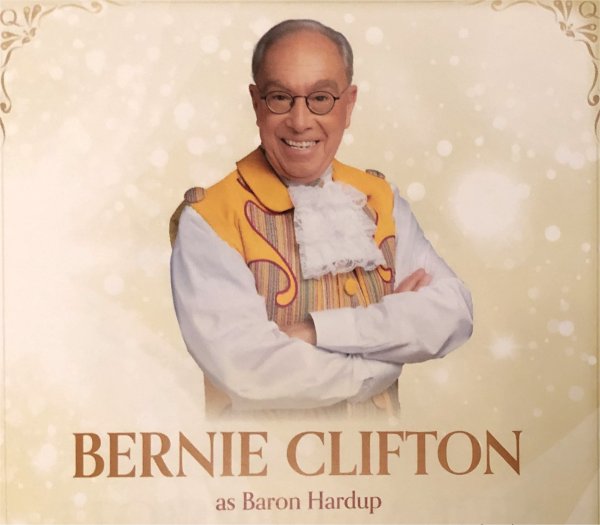

The 82-year-old British comedian and singer is two days from the end of a three-week pantomime run in Cinderella playing the befuddled Baron Hardup. Pantomime, often abbreviated to “panto,” is an English institution, taking fairy tales and loading them with innuendo, audience call-and-response, drag queens, and humor with more corn than an Iowan field. Throw in magic tricks and the occasional earnest ballad and it’s two hours of family entertainment. It’s the perfect vehicle for Bernie’s routine that mixes prop humor and groan-worthy jokes with soulful singing.

“I can see the winning post,” he says as we meet for coffee at the hotel where he’s staying during the panto run, “but so can the germs, they’re coming running. Panto is great, but it is draining, the old bones are feeling the effect and it does chip away at your energy.”

Even though exhaustion is creeping in, Bernie is eager to talk.

We find a comfortable window seat in the plush lounge called Snobs at the Kingston Theatre Hotel, less than a minute’s walk from the Hull New Theatre where Cinderella is playing. Hull’s a city on England’s northeast coast and I’m back to visit my parents for the holidays. When I found out Bernie was here, I couldn’t resist requesting an interview. My dad managed variety clubs of the type Bernie played in, so I was very familiar with Bernie and his other cabaret performing peers.

He greets me with a strong handshake and apologizes as he pops a lozenge to sooth his throat, his voice slightly hoarse — the only giveaway the show’s starting to take a toll. Next week he’ll be able to relax on a holiday to visit his son who lives in Dubai. A respite is deserved for a man whose career spans many decades, a performer many Brits know for his slapstick routine riding a fake ostrich, but whose biography deserves discussion of so much more.

Bernie planned to be in Dubai weeks ago, but joined Cinderella after the death of the comedian previously slated to play Baron Hardup. Barry Elliott, one half of a comedy duo known as the Chuckle Brothers, died in August. Taking on his role was bittersweet for Bernie, who knew Barry and his brother Paul. “It’s poignant that I’m only here because we’ve lost Barry. And that’s kind of sobering. But that’s way the business is, as we all know the show must go on.”

I suggest that Bernie’s sprightly farcical comedy serves as a tribute to his late friend, and he nods, pauses for a moment, his eyes watering. “Oh, yes, definitely” he says softly.

Then he smiles, and laughs as he describes the on-stage antics in the show. His fake ostrich Oswald, a trademark piece of his routine, makes an appearance. It’s a huge costume of a ridiculous-looking bird with big googly eyes. When Bernie wears it, his legs look they belong to the ostrich, and two fake legs draped down its body make it appear as if Bernie’s actually riding it. This lets him perform all manner of sight gags racing around the stage, pecking at people and props, causing mayhem.

But the ostrich is just a small part of Bernie’s panto performance. There’s an extended scene with an inflatable diving suit more than 15 feet tall, which makes exaggerated fart noises as Bernie struggles to deflate it. The humor might seem sophomoric, but it’s perfectly fitting for the show.

He also joins in with the wisecracks that are just as much a key part of the show, the kind of humor that includes the one-liner “Living in Hull is like a fairy tale, it’s Grimm.”

Even after tearing around the stage with a madcap routine that would exhaust someone half his age, Bernie still has the zest to belt out an impressive rendition of “Love Changes Everything” from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Aspects of Love. If that creates questions about what a diving suit and a West End show have to do with Cinderella, don’t worry about it. Panto is a deliberately anachronistic affair, as long as people laugh it doesn’t have to make sense.

“It’s the greatest fun,” Bernie says with a proud smile. “Where else can you take three generations of the same family and be entertained? Nowhere. And that’s the joy for me. To see parents and children and grandchildren all laughing — not to get too profound, but to hear the laughter of a child is a precious thing, and backstage we always say we’re a blessed crowd.”

He stops again, his eyes slightly glossy. I’m learning quickly that Bernie is a man who doesn’t hide his emotions, and his earnestness wins me over immediately. And even when the conversation takes a more serious turn, there’s always a twinkle in his eye and a gag at the ready. Sure enough, seconds later he jokes in urging me to get a ticket to a matinee performance. “Get the early show if you can, look at the state of me, I’m not even buying green bananas anymore.”

We’re the only customers at the hotel bar, not surprising given it’s around 10.30am on Friday. The upside is a quiet room that makes it easy to talk. The downside is food won’t be served for a couple hours, so today it’s drinking coffee with a stranger, no dining.

Bernie looks much younger than his 82 years. He’s dressed casually in a black t-shirt and plaid shirt, an expressive face framed by a pair of thick glasses. During our time together he leans back in his chair, laid back and projecting comfort. Most importantly, he’s a chatty man even when tired, all I have to do is nudge gently and the stories about his career tumble out.

He was born Bernard Quinn in 1936 in St. Helens in northwest England. “59 Charles Street,” he recalls. “During the war, a bomb missed us by 20 yards. The people at 63 were killed.”

After World War II and once he was of working age, Bernie tried a variety of occupations. In particular he remembers his time as a plumber, because he was impressed by some of the acoustics in the bathrooms where he worked. He’d liked singing since childhood, thought he had a good voice, and while doing his job would entertain himself by belting out tunes.

Eventually he decided to try singing at working men’s clubs — places where laborers would gather and listen to performers. The no-nonsense audience was a baptism by fire for entertainers, requiring the acts to have a thick skin. “But there was also a great atmosphere of anarchy and comedy,” says Bernie. “And I got welded to that mischief, that humor.”

With a show that blended jokes and singing, he would get four pounds (roughly six dollars) for “a noon and night,” which he describes as performing for working class men at a daytime show, and if the act got a good reaction then returning at night to repeat the act for the men’s wives.

Soon he realized that prop comedy could be a unique selling point. “I’d be in a little pub or club signing and there’d be stuff around, like a piano stool, I’d lift it up and all there’d be these reams of music and I’d start to muck about with them, or there’d be curtains and I could…” and then mimics wrapping himself up in curtains with an exasperated look on his face. “I had a gift of working visually, so gradually it became a tightrope between the singing and the comedy.”

Bernie then met his wife and settled in the northern town of Doncaster, creating a business with a friend selling electrical appliances in the 1960s. “We were virtually bankrupt the whole time,” he says with a chuckle at the memory. “But at the same time I was doing the clubs at night.”

Although the money wasn’t stellar, he admits having “an addiction to applause” that convinced him a full-time performing career might be feasible. “I was really doing what I wanted, and I was becoming successful in the minor leagues. As you worked up the ladder to better clubs you could get the aspiration to appear on television,” he says in-between sips of coffee.

In 1971, Bernie’s growing career helped him secure a spot on a BBC TV show called The Good Old Days, featuring variety and music hall performers. “To get on that meant you were really on your way,” he explains. It was his first of what would become countless TV appearances.

Topping the bill was comedian Les Dawson, by then already a household name in Britain who made his name appearing on the TV show Opportunity Knocks in 1967 — a decades-old precursor to the likes of Britain’s Got Talent. Les watched Bernie perform his mix of singing and jokes, then pulled him to one side after. “He said, ‘You’ve got something lad, but you’re just doing what all the others are doing. Why don’t you find yourself an identity? What do you like?’ And I told him I love working with props and being visual, and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you be a prop comic?’ And I really took him at his word and from that day I had to have props. I’d found my path.”

In addition to the ostrich costume, Bernie had an attic’s worth of props for his routine including biscuit tins he’d use for dancing shoes, empty gas cylinders he’d wear under a cloak “like a walking industrial disaster zone,” a puppet cat for his shoulder, and many more.

His self-described “big breakthrough” on TV was in 1975, appearing as the resident guest on singer Lulu’s series that featured songs and skits. That visibility got him other work, including two series of children’s show Crackerjack! with its mix of comedy plays, games, songs, and other routines. Bernie and Oswald the Ostrich were starting to become household names.

The man-and-puppet pair exploded into popularity in 1979, when they appeared on stage at London’s Theatre Royal for the Royal Variety Performance — a variety show hosted by Queen Elizabeth II featuring singers, actors, comedians and other raising money for charity. “I packed as much of my act as I could into my eight minute spot, and just exploded onto the stage with the ostrich like a dervish,” Bernie recalls “The queen was dabbing away tears of laughter.”

It’s a night he says changed his life, and led to steady work ever since. Yet it also firmly established Bernie and Oswald as a duo rather than Bernie Clifton, stand-alone performer. I wonder whether he has any resentment to the long-running association with the bird. He doesn’t.

“No, no, no,” he says, smiling warmly. “I’m too much of a realist. Okay, it’s a label, and I’m sure it’s on my obituary somewhere, but I often think where would I be without it? There were dozens and dozens of very talented comedians, joke tellers, having good careers but they never actually got a proper breakthrough. So I think [the ostrich] did give me some identity.”

The inspiration for Oswald dates back to the 1800s and the act of Samuel Joseph Torr, a music hall performer who gained notoriety for exhibiting the “Elephant Man” Joseph Merrick around the country. One of Torr’s routines was a dance with his “daddy-o,” a papier-mâché costume that gave the appearance of Torr sitting on a dummy’s back while it danced. Bernie used that idea and instead came up with the concept of riding around on a goofy-looking ostrich. “I suppose that points out there’s nothing new, everything’s regurgitated, but it got me on another level.”

Although Bernie has never struggled to find work, he says the advent of darker, alternative comedy in the 1980s did lead to some ebbs and flows getting gigs. Old school cabaret-style performers “became kind of stigmatized,” he says, “I think a lot of warmth went out of comedy. The older comics, there was that lovely thing about them, they could be your daft uncle. And all of a sudden that became anathema to the next generation. I was always family oriented.”

In this decade his stint on Crackerjack! ended, and the new TV stars were acts like comedian Ben Elton with diatribes against Margaret Thatcher’s government. Although Bernie was on screen less, he remained popular, performing in pantos for summer seasons that could last up to 20 weeks. “I was somebody people could take their kids and parents to see, so I was never affected [by alternative comedy] the way a standup comedian would have been.”

Still, he confesses that the older generation of music hall comedians weren’t impressed by the foul language and informal dress of the newcomers. “I think they were resented by all of us because we used to perform in proper suits and bow ties, and these guys came along in ripped jeans and t-shirts, looking they just fell out of bed or just walked in off the street. There used to be a popular phrase among my generation: ‘Alternative comedy, it’s comedy without laughter,” he tells me. “But that was our only defense, they were taking over the world and we were yesterday’s men.”

In the 1990s, Bernie continued to perform his zany routines but instead of doing several months in one location he found more work doing residencies at different holiday centers around the United Kingdom. “So you’d start a show in Skegness, then drive overnight to Scotland, then drive south overnight to Wales, I was like long-distance lorry drive with an act in the back. But the remuneration was very good, and I had a work ethic that said to do it year after year after year.”

This lifestyle continued through to the next century, and in 2005 Bernie experienced a resurgence in recognition with his appearance in a music video for Tony Christie’s “Is This the Way to Amarillo?” Comedian Peter Kay, at the time in his 30s, is a huge fan of variety acts like Bernie and other family-friendly performers, and gathered as many as he could for the video. They all mimed along to the song, released to raise funds for the charity Comic Relief. About halfway through the video Bernie appears, riding Oswald the ostrich as he marches along with Kay.

Among his recent work, Bernie for several years has hosted Live-ish on BBC Radio Sheffield, talking with a panel of guests in front of a live audience about the week’s events.

It’s thanks to the radio show that he also has yet another unusual line item on his resume; performing trombone for the England Band, the official brass band that travels the world supporting the national football team. Bernie doesn’t play the trombone, but the band leader was so eager to have him be part of it he wrote instructions down for the slide positions to play tunes like “Rule Britannia” and the theme from the movie The Great Escape. “It’s so fun because I can play just looking at that, so I travel the world carrying a trombone I can’t really play.”

Even with the radio show, panto every year, and other performances, Bernie still found time this decade for appearances on two reality shows that gained much publicity.

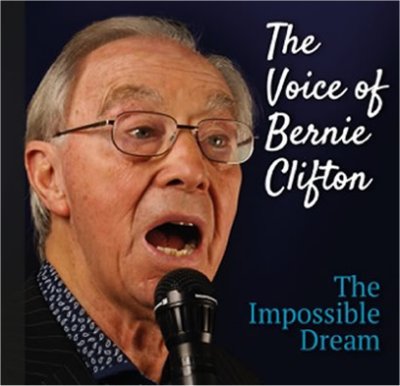

The first was in 2016 for The Voice, a show where four successful musicians sit in comically large red chairs with their backs to a stage. Members of the public aspiring to make it in the music industry then step on to the stage and perform. If any of the musicians rotate their chairs, that means they want to work with the performer as the show progresses to help them try winning the contest. If none of the chairs turn round in the blind audition, the singer is out.

Bernie reminds that he’s always loved singing as “an aspiring tenor,” and says he’s had lessons all his life. A few years ago he got a new vocal coach, David Maxwell Anderson, who helped him hit previously impossible notes. “He produced this timber in my voice that I always felt was there but hadn’t been revealed. And then I thought what am I going to do with this?”

Watching the BBC show The Voice, he liked the fact the judges appeared positive and encouraging to the performers. So, at 79, Bernie applied under his birth name of Bernard Quinn, not telling his family, agent, or anyone else about it. He recalls standing in the queue for the auditions in London, the only septuagenarian amid a throng of teenagers. The first pre-show audition went well, and he got to about the third preparatory audition before someone on the crew realized who Bernie was. He admitted he was “that guy with the ostrich,” but still made it on screen.

For his audition he performed “The Impossible Dream” from the musical Man of La Mancha for the judges. Although none turned their chairs, Bernie got a standing ovation from the audience. And when judge Ricky Wilson, lead singer of the Kaiser Chiefs, turned his chair around he was surprised to recognize Bernie. He’d watched the funnyman in person as a child and watched him run around with Oswald the Ostrich, and cried as he reminisced with Bernie.

Inspired by The Voice, he put together the album The Voice of Bernie Clifton: The Impossible Dream which includes the titular number and 16 other ballads that show off his impressive voice, such as “Wind Beneath My Wings, “Danny Boy,” and “Lady in Red.”

Just two years later, another reality show called — this time in Las Vegas.

Television network ITV signed Bernie for Last Laugh in Vegas, a five-part documentary in which a group of cabaret acts from the 1970s were reunited to put on a special one-off performance in Sin City. “I heard on the grapevine that because they saw me on The Voice it reminded them that I was still around, and that I could sing as well,” he says. The group of nine men and women lived in a house together, going through intensive training for their big night.

Watching the show is like Big Brother but with more puns and singing of old standards. “It was hysterical,” Bernie says with a laugh. “Here’s people I’ve known all my life but never shared a kitchen with,” he adds, telling me for example about singer Jess Conrad who was used to being waited on “hand and foot” by his wife and didn’t know how to open a packet of cornflakes. Or crooner Kenny Lynch who would hang out in the kitchen swearing to himself.

They performed the show last October and the TV series aired in April. Bernie brought the ostrich to Vegas and trots him across the stage before doing some other gags, including the deflating diving suit routine and lines like “I’m still making love at 81, which is great because I live across the street at 64.”

But he also sang Whitney Houston’s “One Moment in Time,” becoming the first of the acts to get a standing ovation — something that made him cry.

Bernie chokes up talking at the memory of the night, and the experience gave him grist for yet another show.

As our hour together nears its end and Bernie prepares to make the short walk to the theater, he tells me about his new one-man show From Crackerjack! to Las Vegas. He’s already performed it a few times, taking a projector on stage and talking, singing, and making jokes as he shows pictures from his colorful past. He covers everything from first starting out at the working men’s clubs through to his recent TV appearances.

And he’s working on his autobiography covering much of the same ground as the one-man show. “I’m about 70,000 words in but I’m only up to 1980!” he cries in mock panic. I ask what’s his deadline and his eyes dart side to side nervously. “10 years ago,” he laughs.

We get ready to leave our empty coffee cups behind, but before we part Bernie takes a moment to talk about the current state of comedy. He sees the likes of Peter Kay helping to encourage a revival of “warmer” comedy, less swearing and more physical gags and goofy humor. Indeed, Bernie will be performing in a slapstick festival in London in April alongside other show business veterans.

It’s a busy life for anyone, not least an octogenarian.

But it’s clear Bernie wouldn’t have it any other way. Throughout our time together he hasn’t made a single cynical statement, he’s made me laugh multiple times, and he’s been charming company. Perhaps he’s so upbeat because he’s achieved his aspirations; the plumber from St. Helens has gone on to travel the world cracking jokes and singing for a living.

It was a possible dream, and he made it a reality.

Had the pleasure to work with Bernie at Butlins Bognor Regis. What a gentleman. An absolutely fantastic guy. Would love to see him again.

fhzldn