SILVER SPRING, MARYLAND

December 15, 2011

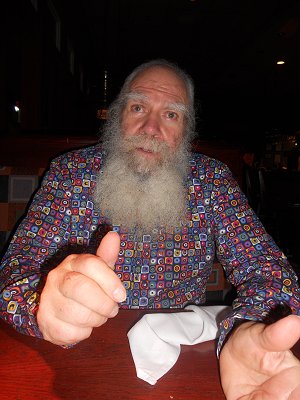

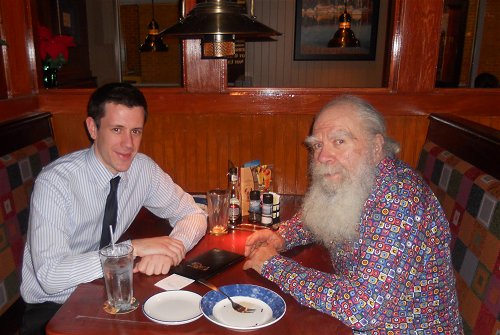

STRANGER: Ed Downey

LOCATION: Red Lobster, 8533 Georgia Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland

THEME: A mid-December dinner with Santa Claus

Christmas brings with it some memorable images. A tree festooned with baubles and tinsel, neatly-wrapped parcels sitting underneath. Stockings hanging from a fireplace. Cuban singing curiosity Margarita Pracatan and I mangling a medley of festive songs.

Santa Claus is right up there alongside them.

The jolly, overweight man in the red-and-white suit is someone many children are taught to idolize from an early age. After all, this is the man who brought young Anthony his Amstrad CPC 6128 computer. That machine was a lot of fun, even if you had to wait 30 minutes for the game cassettes to load. So I’m grateful to Santa and was happy to get dinner with him.

Or, more accurately with Ed Downey. For the last 29 years Ed has been performing as Santa under the awning of his one-man company Santa Claus Productions.

Ed, 78, now lives in Maryland but his colorful past has taken him around the world and across the States, working all manner of jobs. As I’d learn over a fish supper at a local chain of the Red Lobster restaurant brand, there’s far more to Mr. Downey than just Santa.

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, he went to several small colleges in the state, spending part of his education at Central Missouri State College and the last two years at Missouri University in Columbia. After graduating he served two years in the army “just to get it over with” and then enrolled in a social worker course at Washington University in St. Louis.

He decided to do social work after several summers working as a child camp counselor, where he was “always inventing new things to do, special events and stuff.” He preferred working with the teenagers — the other counselors saw them as a challenge, but he didn’t. He’d work with them, offer advice, ask them about what they planned to do for a living.

His director at one of the camps was impressed with how Ed managed to entertain the teenagers with activities and educate them. Ed said he was told, “’You’re good, but if you become a social worker then you’d do the same things, but the goal is not to have a good activity. It’s to get people to interact in a way that’s beneficial to their lives.’” The director recommended he study to become a social worker. And that’s how Ed ended up at Washington University.

After graduation he worked as a probation officer and had a “very successful” run until the Christian businessmen’s committee that ran the organization he worked for took him out to lunch one day. Over a meal, they told him how happy they were that Ed was spreading the word of God to the troubled young people on probation and using religion to get families back together. While Ed was certainly reuniting families and improving lives, he wasn’t do so with a Christian bent. “I wasn’t going to lie to them,” he said, and told them that his work didn’t involve religion. “They pretty soon de-funded my program.”

So he went to work for a settlement house, which got its name from the early days in the States when large groups of immigrants would settle in one place. They either couldn’t speak English, or didn’t know basic things like how to use an elevator. To them, life was only work. Rich but kindhearted people in the suburbs then decided to help them by establishing a house where they could tutor the foreigners and integrate them into America.

Grace Hill House in St. Louis was one such place, in a Polish district. Ed worked with men that toiled as skippers. “They didn’t consider themselves living, they just were working up here. My job was to help them see they’re living here,” Ed said. He did this by offering all manner of activities, education and advice. His efforts were so successful that eventually the people he worked with all moved to the formerly out-of-reach affluent suburbs.

Ed was group director at Grace Hill, but left after two-and-a-half years when his bosses wouldn’t let him accrue his vacation time for one long holiday.

So he moved on to yet another job, this time applying for the Peace Corps in 1964. He admits that going in to the intensive selection process he probably didn’t stand a shot, but tried anyway. “They just wanted somebody that is not left wing or right wing or introvert or extrovert, they just wanted someone middle of the road, and of course that’s not me.”

He made the first round of the selection process, but got dropped in round two. Ed thinks it’s partly because his ideas were outlandish to the supervisors — things like setting up community groups to embolden the women of more restrictive countries.

“I knew I had pushed too many peoples’ buttons”

The other reason Ed thinks he got cut is that he stood up to defend the honor of a fellow applicant, Sam, who had been let go. The officials ran down a list of all the things Sam had done wrong. But Ed knew they were false and at a large group meeting challenged the higher-ups on each charge. At that point, “I knew I had pushed too many peoples’ buttons.”

If he’d made it into the Peace Corps, he would have been posted in Brazil. Because he knew a lot about the country due to his training, he decided to visit it.

Hitchhiking and taking third-class buses, he made his way down to Brazil, where he had plenty of “adventures” — the very word bringing a smile to his face. One memory that stands out for him is a night he and some travelers hid out at Macchu Picchu until after the guides and guards left. They spent the night under a thatch roof on the site, which kept them dry from heavy rains. Then the rains stopped and they looked in awe at a double rainbow over the mountains. “It was so romantic, the whole thing. We just felt like we were centuries old,” Ed said.

After Brazil he boarded a boat and worked on it all the way to Hamburg, Germany. Eventually he wound up back in the States and took on odd jobs in New York City.

As I’d shortly learn, the next chunk of Ed’s life was dominated by the “American Odyssey,” a novel concept for an education course that he had been crafting in his mind.

Before Ed could divulge the full details, our waiter arrived with two garden salads.

They were pretty basic — clumps of lettuce, slices of tomato, a few croutons and some sliced onion. I definitely got the better end of the bargain because Ed’s tomato slices looked more like whatever was left after the slicing was done and the decent stuff got served to other patrons.

Sadly, the salad was entirely uneventful and had probably been sitting out for a while. On the bright side, I had some vinaigrette dressing and pretty much drowned the dish with it to try and create something approximating flavor. I found the bread rolls were buttery and surprisingly delicious, so with my salad adrift in a balsamic sea and a mouthful of bread, I ate on.

With my face stuffed full of food, Ed was able to continue his life story.

His various travels and jobs had given him plenty of real-life education, and I’m sure there’s a cliché about stuff you can’t learn in books that would be apropos here. Ed wanted to use that knowledge to craft an American Odyssey course in which a group of 12 would take two years of college doing a wide variety of experiences across America. Each of the 12 members of the group would be studying a different major — art, law, whatever — and wherever they’d go, the students would use their experiences to help each other learn something new about each others’ majors.

Ed pitched the idea to alternative colleges, and almost got in at one place that was offering a masters’ degree in current anthropology where people were looking at humans nowadays as anthropologists, with people writing studies on subjects like the Coke bottle or Batman.

“My wife wanted the little house and picket fence”

The dean of the college was sold on Ed’s idea, helping him set up an advisory committee with various faculty members. Things were going well. Then one day the government started offering grants for innovative education programs. The dean said the faculty members on Ed’s panel would want those grants for their own programs, and Ed was out.

That prompted him to relocate to Miami in 1972, the year that the Democratic and Republican parties were both holding their presidential conventions in town. Ed camped out with the alternative crowd that was demonstrating. It’s where he met his (now ex) wife. She was observing the events as part of the Community for Creative Nonviolence — if someone in either the crowd or among the police did something violent or otherwise out of line, the group would try to stop it.

When they met, she asked Ed if he’d seen Miami. He said no. So she took him on a bike tour. “After that, I went over to her house, and I never left.” They were in Miami for about four months.

He tried once again to get his American Odyssey course part of the offerings at a college in Miami-Dade county, but Ed said the dean found every problem possible with the plan. In a move that seems to be how he operates his life, Ed didn’t wallow in defeat. Instead he took his wife and four friends in a van and went on a true American road trip, moving from city to city in search of new adventures.

Eventually they made their way to Washington, DC. It was in the nation’s capital city that Ed met people interested in his American Odyssey plan. Ed tried to get sponsors for his course, but said that at this point his wife had had enough of travel and seeing the country. “She was really threatened by it. She wanted a marriage with the little house with the picket fence.”

Ed wanted the same, to an extent. He argued that if his course took off, they could live in a big house at any college, with a huge living room and dining room for students and others to hang out. They disagreed on that basic idea, and eventually the couple divorced.

It seems like a sad tale of a dream unfulfilled. However, Ed is nothing but upbeat. Throughout dinner he was relentlessly cheerful, and he uses his experiences to tell great stories and offer advice to a simple-minded reporter like myself. He’s used everything in his life to learn from it — something that even applies to how he found himself working as Santa Claus.

Ed started growing his beard out in the 1960s. In the early 1980s a friend asked whether he’d be a Santa for their party. He was delighted to help out, and bought a costume. That’s how he got started, and now when December rolls around, it’s usually a full-time gig.

In the days before the internet, Ed advertised in newspapers to get noticed. Then word of mouth helped him get more jobs.

Ed prefers being a self-employed Santa rather than working for a company that might place him at a mall. He tried that a couple of times — once at the Tyson’s Corner mall in Virginia and another at Saks Fifth Avenue in Bethesda, Maryland. Store Santas make more money than the self-employed ones, making about $45 an hour, but they have to work 8 to 10 hours a day, 7 days a week. It can be a grueling schedule, and often one that requires them to leave their hometowns temporarily.

“You usually cannot get a job in your own city” to be a store Santa, Ed explained. I asked him whether that’s to keep up the mystique and avoid having children in town see the Santa walk around in his day clothes. Apparently not. The biggest concern for the companies that hire professional Santas are distractions from family and friends. “They want you there seven days a week. If they go to a new city and live in a hotel, they don’t have those outside distractions.”

Being self-employed, Ed doesn’t have to worry about those restrictions. Instead he offers his services as a one-off Santa that has a real beard, tells stories, does magic, and entertains the crowds. “I know what I can do, and I do it well,” Ed said.

His work includes corporate functions, family parties, and plenty more. It can be a busy time. One year he worked seven jobs on Christmas Eve, starting at 10 in the morning. An especially good year can bring in more than $8,000 from bookings.

There have been some memorable events. His most recent job was dressing up as Santa to visit a terminally ill child at Georgetown Hospital in Washington, DC, who adored Santa Claus and Christmas. Apparently a social worker at the hospital got in touch with Ed after visiting his website and seeing the letters “MSW” on his resume — Master of Social Work. When he got to the child’s room, Ed used his social worker skills to interact with the family and get them all together for a picture.

“As Santa, children idolize you”

Another job that sticks in his mind took place over several years. A Hispanic father would call Ed over each Christmas Eve, telling him to go to a station wagon outside the house and fill up his bag with toys. Ed, as Santa, would then walk inside and lay the presents out under the trees. Then he’d go and eat a plate of milk and cookies left out for him by the children of the house. All the time the children of the house would be watching him from the staircase, transfixed. “As I left, I’d ring my bell and say, ‘Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night.’ They were totally convinced.”

What about the stereotypical image of children pulling on Santa’s beard? Apparently they don’t even bother with Ed because it’s obvious that his beard is real. The only exceptions he’s had in 29 years were a 13-year-old that thought pulling on the beard was part of the meeting Santa ritual, and when he meets toddlers. “They grab it and you have to pry their hands off.”

Mostly children just “idolize you,” Ed said. Even the adults take a shine to him, and he gets plenty of dances with ladies at office Christmas parties. “Sometimes I’ll even break character for a second and tell them, ‘And I get paid to do this,’” he said with a smile.

I asked Ed whether, like most jobs, there are downsides. It was refreshing to see that he actually had to pause and think about his answer. None came to him right away.

It was probably a good thing that the conversation paused while he thought, because our main courses arrived. Based off my experience at Red Lobster that night, we were probably lucky getting our entrees because we wouldn’t see or hear from our waiters for another hour. Not attentive service, and hard to excuse given that the place wasn’t busy.

Ed went for a healthy option of grilled salmon with broccoli. He said he eats a lot of plain fish, and he spoke favorably of his meal.

I wasn’t so lucky with the fish and chips.

It was a hefty lump of haddock, but the chips were tiny little twigs of potato and the overriding theme of the dish seemed to be salt. I couldn’t really taste the batter, the fish or the potatoes. All I could taste was sodium. I would say the dish was a big letdown, but I’ve come to except bad fish and chips in the States. Alas, not every meal can be a winner. Good thing late December took me back (temporarily) to England, and big hearty servings of flavorful fish and chips.

As I ate, Ed finally came up with an answer to my questions about downsides to his work. Some families just want Ed to show up as a de facto babysitter. And it can be tough for him to visit households where the husbands don’t take an interest in their children, which he says happens with “the very poor and the very rich. They don’t take time with their kids. That’s hard for me to see.”

This year has also been a little difficult for Ed’s work as he moved house and had to spend a lot of time getting his old place in order so he could hand it over to the landlord. He didn’t even get round to calling last year’s clients, and is more likely to take in $3,000 this year than the typical $8,000.

Still, he’s looking forward rather than backward, and is planning to update his self-designed website for the next festive season. He took free computer classes with Apple and learned how to build his own presence on the web. “It doesn’t look like any other site you’ve ever seen,” he said. He’s right. It’s a very colorful website that’s well worth a visit.

“I haven’t marketed the site yet. Next year I will because I’ve got the site, I just didn’t have the time this year to do it,” Ed said. And he’s got some unique things to promote.

Unlike the polished Santas with pristine white beards and baritone voices, Ed aims to be “very believable.” His hat is lined with real fox fur — I can attest it’s luxurious to the touch — and doesn’t look like a generic costume. “I want to really look like I just arrived from the North Pole after a hard day’s work,” Ed said. While some people prefer the more theatrical-looking Santas, Ed’s there to provide a down-to-Earth, believable look.

No matter where his gigs might take him, there’s one constant he strives for. “I radiate love, like they’re the only person in my whole life.”

A nice thought to end on for the holiday season.

I loved your story about Ed. I rented a room from him in the early ’80’s. He was a larger than life character, and a beautiful blossom on the rosebush of humanity.

Thanks for sharing a meal with him, and with us.

Martin

3bgsrp

744n08

5h7ee9