WASHINGTON, DC

October 13, 2019

STRANGER: Sampson McCormick

LOCATION: Busboys & Poets, 450 K Street NW, Washington, DC

THEME: An activist gay black comedian talks about his career

“I needed to get some more DC in my life,” says Sampson McCormick. “DC has its own flavor, I have to come get some of that flavor every now and then to keep me sane.”

The 33-year-old comedian, born in the city but now living in Los Angeles, is back in his hometown for several days, his trip centered around a gig at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Oprah Winfrey Museum talking about gay history. “I’m the first LGBT comedian they’ve ever had to perform in there,” he says with pride.

We’re meeting for dinner a few days before the show, and Sampson is unsure exactly what he’s going to talk about on stage. “When I get up there I let the spirit move through me, whatever comes to me,” he tells me, but there are some things he will and won’t talk about. “I’m going to the talk about religion, but I usually don’t say the T word, Trump, but I will talk about the state of America as it is now, things that queer people of color go through. A lot of the issues of the day revolve around race relations, and I’m very honest about it and I think people see I’m just up there to share my truth.”

As forthright as he plans to be, Sampson also says his strong opinions and “stubborn” nature mean he doesn’t moderate his act just to get jobs. And he tells me he’s lost out on gigs like a role on Netflix’s Queer Eye and late night television as a result.

“I wanted to get on late night, and I was told no, they said I was too black and too gay, and you gotta choose one, we’re not saying you aren’t funny, we’re saying this needs to be suitable for mainstream America,” Sampson tells me from across the dinner table, rolling his eyes at the memory. “I said that sucks but I’m gonna show you, and I don’t really beg people too much for opportunities.”

A similar thing happened when auditioning for Queer Eye; Sampson says he was vying for the culture expert role that ultimately went to Karamo Brown. “The person who was doing the interviews thought that I’d be great, but when they sat down and listened to what all that I had said she called me back and said, ‘I want you to be honest but I want you to change some of how you approach views on race and sexuality.’ But I’m not good at doing it, but that’s what Hollywood is. And so she called me and she said, ‘I love you, I think you’re incredible, but the producers think that you are just going to cause too much riffraff on the show,” he tell me. “And I had to accept that.”

Does he regret sticking to his principles and missing out on what’s become a global phenomenon? “Sometimes,” he says. “But ultimately I have to look at things like that and think that 10 years from now, considering all the other things that I worked for, as persistent as I am, as dedicated as I am, I ask myself what is the bigger picture and I do realize that just because this happened it’s not the end of the world.”

Instead, he charts his own course and a look at his output over roughly 20 years would suggest it’s reaping rewards. He regularly travels across the country performing in mainstream venues. He’s got an active YouTube page with almost 12,000 followers where he posts standup routines, skits, and feature-length LGBT-themed movies. And he finds time for more serious work including activism on issues like homophobia in the church and HIV in the gay community.

“As many ‘noes’ as I hear, I’ve created a lot of opportunities,” he says.

Because Sampson works without major Hollywood representation, he says that it allows him to perform without restriction. He works with a small squad; people who run his social media, answer emails, edit and produce his online content, a makeup artist on both the east and west coast, and more. “One of the things I’m most proud of is I’ve never waited for anybody to give me an opportunity,” he says.

Although he’s occasionally reached out to agents and managers, Sampson adds that he’s established a solid career as an independent artist. “The thing about the business after you do it for so long, you learn how to read paperwork, you have your own team, you know what to look for. You hear about so many people who make their living dictating to you how the business is done, they don’t want nobody to come in and tell them ‘I don’t like that.’ I still manage to create things that are very successful.”

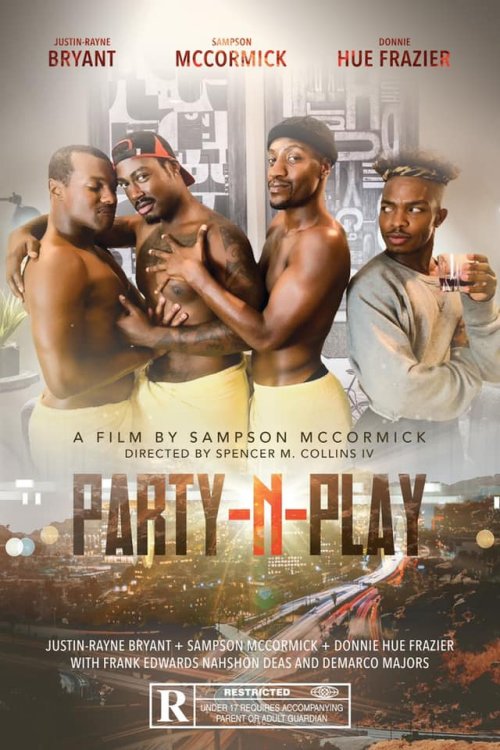

Most recently he released a roughly 45-minute film, Party-N-Play, which is a comedy thriller about an obsessed Beyonce fan. It’s a good example of Sampson’s unique humor that touches on his experiences growing up black and queer, mixed in with some pop culture commentary. “It’s very experimental and outrageous and I had to learn and not care if a family member saw it.” After just four days online it’s at almost 5,000 views.

Browse his YouTube page and you’ll see a wide variety of material that also includes a 2017 documentary A Tough Act to Follow, featuring interviews with queer people of color in the entertainment industry; standup routines that fluctuate between serious topics like “Black Men Who Hate Gay People” and “Pray The Gay Away” to more playful bits about sexual positions or taking a visit to a bathhouse; and other one-off videos like talking about whatever’s on his mind or the experience of taking an HIV test.

“I think as comics most of us like to step outside of the comic role to show a more dramatic type sometimes,” he says. For people who might just want their standups to only crack jokes and not touch on sensitive subjects, Sampson’s not interested.

“I’ve always talked about things that affect queer people of color, one of those things is the church, and whenever I’m in the South I’ve had black gay people get up and walk out of the show and confront me online about it or after a show in the parking lot. And I say, You can get up and walk out of my show but you can’t get up and walk out of a church that’s telling you you’re going to hell for how you love, what is that?’”

Sampson defines his current performance style as “speaking truth to things that affect us and not mincing words,” but says it took years to get to that point. When he started out in comedy he went for easy jokes (think “Your momma is so fat…”) and then he veered to the absurd, trying to find whatever would get the biggest laugh in the room. From there he evolved to “mixing silly with serious” before working in more activist, political bits to his routines that touched on his life experiences.

And he points to his often sell-out tours of venues in conservative states as proof he has broad appeal, despite the doubts of those like the late night producers who thought he was too gay and too black for their mainstream audiences. “I go to Billings, Montana, to play the casinos, I go to Biloxi, Mississippi, I go to Des Moines, I go to Maine, different parts of Florida, and people come out to see those shows. Some people come cause they’ve heard of me, other people hear there’s a gay black comedian and they’re probably think they’re coming to a circus, and then they come and I’ve connected with those people so thoroughly,” he says.

He recalls shows in the deep South where he couldn’t gauge how the audience would react, yet they ended on a positive note. “These are rednecks, or people who look at BET and only think that we walk around with chains on, and they see me and they say wow, that was really relatable. I’ve heard a couple rednecks say, ‘I don’t like queers or blacks but you a pretty funny motherfucker’ or ‘I related to a lot of things you said, I was laughing at that shit like I live it. That don’t make me gay do it?’”

With a boisterous laugh, Sampson cackles at the memory. He’s got a mischievous smile and the engaging charisma of a natural performer. For the almost two hours we’re sitting next to each other he acts like we’re the only people in the busy dining room, and he’s as inquisitive about my life as I am learning about how he built his career.

We’re dining at Busboys & Poets, a restaurant and book store with several locations in the District. It’s packed this Sunday night, and there’s a frenetic energy in the air that belies the laid-back, warm soothing colors of the main dining room. As a result, service is spotty at best, and it takes an inordinate amount of time for our food to arrive.

When it does, I can’t say it was worth the wait.

My fried chicken, which is served with a herb mushroom cream sauce, mashed potatoes, and collard greens, is lukewarm and too chewy, and there’s so little sauce I wonder if there’s a sauce boat that set sail elsewhere.

Sampson’s eating the Salad Niçoise: pan-seared tuna, mixed greens, fingerling potatoes, green beans, boiled eggs, kalamata olives, lemon herb vinaigrette, and a crostini baguette. I’m jealous as soon as the server sets the plate down. Everything looks fresh and tasty, and he barely leaves a scrap by the end of the meal.

In-between bites, Sampson tells me that he has been hustling on his own for work since childhood, when he started out at comedy clubs in his teens as a way to cope with physical and verbal abuse at home and school.

“When I got bullied and stuff when I was growing up, as suicidal as I was, as hopeless as I was, as depressed as I would be to exist — cause I thought I was a piece of garbage — the one thing that kept me thriving was being able to make jokes about it,” Sampson says. “It felt like I couldn’t do anything right but I think some good came out of it, it really taught me how to take inventory of people and read a room.”

Humor was a defense mechanism against the abuse he was getting, and he used jokes at school to win the bullies over. At home he kept his head down when possible, speaking little and instead turning to creative writing to express his thoughts. When I ask whether his parents supported this, he shakes his head. “So I really became creative out of rebellion. I’ve always been a rebellious person, and when you are brought up with restrictions like that, you learn how to navigate those restrictions to find your freedom.”

At school, his teachers read and liked Sampson’s work, which often used humor, and encouraged him to experiment with it. The first ever standup show he did was in his fifth grade class room, roasting the other kids’ mothers. “My teachers were the ones who said I knew how to do comedy. I had grown up looking at Whoopi Goldberg and Joan Rivers and Arsenio Hall and In Living Color, I loved comedy but I didn’t know it was something I could do, I thought you had be famous to do that.”

When he was 16 he persuaded the owners of the since-closed Teddy’s House of Comedy on 7th and I Street NW to let him in to perform underage. His first gig was “awful, awful, awful,” he confesses. “Jokes like, ‘We’re so poor that the light company came and blew our candles out.’ That was the longest three minutes of my life.”

Even though he bombed, Sampson persisted because he felt “deep down” that he’d found his calling — and a mugging helped changed his act. After that first show he was robbed at gunpoint and beaten up badly. The next week he went back to Teddy’s and made jokes about what he’d been through and got a standing ovation. He’d tapped into the same defense mechanism from being bullied; take something awful and find the humor in it as a way to cope. “Being brutally honest about things that hurt and sucked helped me relate to people,” he shares, and that’s how his routine evolved.

That’s not to say his standup career was an instant runaway success, and he recalls several other terrible gigs early on. There’s the time at a hotel in the District when his set interrupted a drunk woman’s attempts to grind up on someone, and she was ready to start a brawl when Sampson made fun of her. Or the show for a group of teenagers leaving Child Protective Services who were also ready to start sparring.

But as he honed his craft and focused more on sharing his stories in a relatable way, with humor and heart, Sampson developed a following that has endured.

For years he identified as one of the only out gay black comedians doing the comedy circuits who wasn’t in drag. He started to develop a following and in 2013 moved to San Francisco with the person he was dating at the time. When they broke up in 2017, Sampson relocated to Los Angeles where he still lives, although work has him traveling often.

From his base in the City of Angels, Sampson and his dedicated team work on his various projects, and he always wants to be busy. “I will always be a standup comedian first, but I refer to myself more as an entertainment entrepreneur. I’ll write a script, I’ll produce a web series, I’ll write a book, it’s like having a bunch of pots on one of those big economy stoves,” he says. “I’m a visionary, and that allows me to create.”

Given his strongly held opinions I wonder what he thinks of cancel culture, and the idea of censoring comedy to avoid offending people. “I think there’s a way to approach saying things while also understanding that even if you walk on eggshells. people are going to get upset. Even if you stand up there and talk about rainbows and bunny rabbits they’ll tell you that you left out baby turtles and sunshine,” he says.

Although Sampson enjoys the independence of being his own agent and manager and the freedom of saying whatever he wants, he doesn’t feel that the work he gets necessarily always reflects the years of work he put in with the lonely role of being a gay black comedian. He contrasts that with the success that he sees some younger queer comedians of color getting only a few years after entering the industry.

Sampson says he doesn’t begrudge those younger comics their apparent swift career growth but wonders when he’ll get some credit for what he considers to be a lengthy job of being an out minority comedian. “I’m not gonna lie, like at one time I did get upset because I was like, well shit they’ve been doing it two years, here I’ve been doing it 15 years longer than them and I haven’t gotten the TV gig, I haven’t gotten this and that. But you know, I really had to back up and assess my ego playing a role in this this, and I said some of the fights that I had to fight, I look at a lot of the queer comedians of color that are coming out now, they don’t have to have those fights,” he says.

“I want what’s mine,” he tells me as our dinner nears its end, “so that I can have some of those same experiences. It’s not to walk around and say that I did it, but it’s more so that I have can have more opportunities to develop as an artist. But I am happy to see people getting television exposure and things like that because it reminds me that it’s possible.”

“I would never sit here and take the credit for single-handedly doing it,” he adds, namechecking other queer comedians who’ve been out since the 1980s that he feels “never got their just due” for helping generate acceptance of gays and lesbians, including Tom Ammiano, Marga Gomez, Kate Clinton and Karen Williams. Then he shrugs. “All we can do is keep doing what we do, no matter what anybody does.”

Next year Sampson plans on self-publishing a memoir — opting for that route to avoid any censorship or approval from corporate editors — to share more stories about what it was like for him and his LGBTQ peers when they started out in comedy.

“How many queer comedians of color, and I was one of the first in the country, sit down and tell their stories? I think I’ve earned the right to tell a few of mine.”

weudkz