WASHINGTON, DC

December 19, 2016

STRANGER: W. Ralph Eubanks

LOCATION: Mulebone, 2121 14th Street NW, Washington, DC

THEME: Dining with a writer, educator and scholar on racial issues

Dinner with W. Ralph Eubanks is an education.

Ralph is a writer, scholar and editor, and as a self-described “light-skinned” African-American has a particular passion for the subject of race relations in the United States. In contrast, I’m a pasty-skinned Anglo-Saxon from a northern English city that wasn’t exactly brimming with diversity. So our dinner was illuminating as Ralph walked me through his direct experiences in America’s racist past, as well as his thoughts about its present and the future.

It was mid-December, a few weeks after Donald Trump won the presidency. For months I’d witnessed — both through my professional life as a working reporter and my personal life as a human being — the worst that the election had brought out in some people, and the toll it was taking on my minority friends. And given Ralph’s background it was no small wonder that we spent a good part of our dinner talking about the election, about Trump, about the wink-wink, nudge-nudge encouragement of racism in the election by some of his supporters. There was even a moment where Ralph looked aghast as he recalled his trip to a Trump rally.

Yet despite the intense unease and uncertainty that he and others have expressed ahead of the Trump administration, Ralph is an optimistic man and has used his writing, teaching and studying to try and unearth some of the seeds that have helped racism to grow, and ways to avoid these in the future.

After several months of trying to meet and failing (my fault) we finally managed to arrange dinner at Mule Bone, which replaced the Southern-themed restaurant Eatonville just off U Street in Washington, DC. U Street was once known as “Black Broadway” and was home to Duke Ellington and other musical greats from decades ago in this traditionally African-American city. It’s now home to a lot of somewhat overly priced restaurants and gentrification, including turnover of dining establishments (Eatonville opened in 2009 and closed in early 2016).

Mule Bone is by the same owners, and gets its name from Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes’ three-act play of the same name. As I walked inside I noticed that much of the décor from Eatonville remains, including a sweeping mural of bayou and other Southern imagery that covers one of the walls. I guess the renovations are still ongoing, because the walk to the bathroom still has a massive “Welcome To Eatonville” mural painted on it.

But the menu has been revamped and is now broken down into three “acts,” and after Ralph and I placed our orders — including splitting several dishes — the interview began in earnest.

Ralph recently returned from teaching as the Eudora Welty Visiting Scholar in Southern Studies at Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi. He’s now back in District “trying to figure out what to do next,” he said with a comical sigh.

A major project right now is a book proposal (he’s had a couple of non-fiction works published) about the Mississippi Delta and income inequality. “I think it’s an example of what happens when income inequality becomes institutionalized,” he said, adding that he was inspired to look into how this institutionalized racist inequality came to be, and why it persisted.

The genesis of the book came from a discussion he’d had in Mississippi a while ago with a worker installing broadband in the Delta, which initially inspired Ralph to pitch a piece for a magazine about how Mississippi remains the least connected and poorest state in the union. But that evolved into analyzing how this disadvantage is tied firmly to the state’s racist past. It’s something he’s very familiar with, as his dad moved there in 1949 and Ralph grew up in the South.

A lot of the Delta land is in private hands or owned by big businesses, he said. Blacks were denied the the ability to purchase much of the land, and the civil rights movement had made racist whites fearful of blacks becoming wealthy and independent. So Mississippi politicians used whatever means they could to keep the Delta land in the hands of whites. But now whites have “basically abandoned the Delta,” said Ralph, and he’s curious about those who remained.

“I’m interested in the people who stayed and their reasons,” he said. He’s found so far that it’s a lot of third generation families. The first generation gets the land, the second generation keeps it, and the third generation either loses it or sells it — but some are staying. Why? It’s something he hopes to answer through his upcoming book, and one for which he doesn’t yet have definitive answers.

Ralph’s parents left the Delta soon after the acquittal of Roy Bryant and his half-brother J. W. Milam in the murder of 14-year-old African-American Emmett Till, who the duo lynched simply because he whistled at a white woman. “That was one of the things that pushed them out of there,” said Ralph. “Plus my father knew he’d never own land, and he wanted to,” he added, noting that his father was able to purchase 80 acres of farm land elsewhere in the state.

The move “changed my life,” he added. A friend of his who grew up in the Delta once suggested to Ralph his life would have been much different if his family had stayed. “And I keep thinking about that, and what my life would have been like.”

As Ralph pondered that thought, our waitress arrived with our starters.

We decided to split two dishes, starting with the pickled fried green tomatoes served with blue cheese sauce. Sometimes fried green tomatoes can lack any real taste, but whatever the kitchen did, it did it well because the tomatoes were fresh and flavorful, and the sauce a perfect complement.

Our other starter was an order of hot catfish tenders served with buttermilk dressing and picked shallots. I’d have been happy to see an entree-sized version of this dish, with its incredibly light breading and fish so tender it practically melted in the mouth. A great start.

Ralph looked around the huge dining room — which also includes a couple of chandeliers — and said it has an air of Southern opulence, particularly the menu. Though there was one item he said he was happy to not see in any of the menu’s acts. “I’ll eat everything except chitlins, I can’t stand the way the smell when they’re being prepared, so I’ve never tried them,” he said with a smile.

Thankfully he was a fan of the food at Mule Bone, so as we made our way through the two starters, Ralph told me about his childhood and his own experiences with racism.

His family already experienced it before he was born, with his mother — who married Ralph’s dad in 1951 — recalling the times in Mississippi where a bell would ring downtown on a Saturday and that’s when all the black people would have to leave. So Ralph was born into a divisive and hateful world, including several years of segregated high school.

Schools were integrated in Mississippi in 1970 and Ralph graduated in 1974, so he only experienced four years of mixed early education. “I was this black kid with a serious Afro,” he said, “But I didn’t really think of colorism until I came to DC. Because I’m light-skinned, people here think I grew up here and had all the customs and privileges of that, but I wasn’t familiar with that at all.”

Instead, his life in Mississippi was one of a world — unimaginable to someone with my background — where having to cope with racism was “just something that we had to do,” as Ralph said. Even his high school reunions were segregated until the 40th reunion two years ago.

After high school, Ralph went to the University of Mississippi studying English and psychology. He had started out in pre-med because his father wanted him to be a doctor, but Ralph’s main passion had long been reading literature. “Growing up on an 80-acre farm in the middle of nowhere, reading for me was my escape to other places,” he said. At university he wrote a paper on the poet Keats in his sophomore year that his professor loved, and encouraged him to focus on his English studies.

He said his late father would have been shocked if he were still alive when Ralph dropped plans for a practical career like medicine. But Ralph’s philosophy is far different thanks to his experiences, and he touts the successful careers of his three children who went to arts schools.

Once he graduated university in 1978, Ralph visited England (he’s a lifelong Anglophile, of which I highly approve) and spent about six weeks traveling the country and visiting literary landmarks, like the poet Yates’ grave. Upon his return he went to graduate school in Michigan studying English literature, wanting the “tighter focus” on English that his undergraduate degree lacked.

He was eventually accepted into the school’s Doctor of Philosophy program but at the same time was offered a job to start work in the publishing sector, and so he took that instead.

Ralph was about to tell me about his early days in the publishing industry when our next act arrived, a salad of smoked beets with house-made ricotta, sorghum-glazed pecans, and sorghum vinaigrette.

The hefty chunks of beetroot were piled high in the center of the plate, and complemented well by the slightly tangy vinaigrette. It was just the right amount of food to tide us over between the small portion — but still great — starters and our looming meat-heavy entrees.

As he reached for a fork to dig into the salad, Ralph continued his narrative from his post-college years, saying he got the initial publishing gig at the American Geophysical Union in DC. He began work as an editorial trainee, and honed his skills working for a couple of scientific associations including a five-year stint at the American Psychological Association. From there he did work for the Taylor & Francis Group publishers, dividing his time between DC and New York for a while.

Eventually, he started work at the Library of Congress and after 18 years he became its director of publishing. He spent much of his time making deals with major trade publishers for the library, everything from calendars to visual books, and he stayed there until 2013.

That’s when he moved to become the editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review at the University of Virginia, which focuses on contemporary literature. “I loved my time at the Library of Congress and it was an impressive building with amazing collections of books, but I really wanted the creative space to write. So when the chance to edit a literary quarterly came up, I thought it fit well with my desire to move in a more literary direction,” Ralph said.

The interest in getting back to a literary focus was due in party to Ralph wanting to build on his experiences writing two books, starting with the 2003 book “Ever Is a Long Time: A Journey Into Mississippi’s Dark Past,” about his experiences growing up in Mississippi. That was followed in 2009 with “The House at the End of the Road: The Story of Three Generations of an Interracial Family in the American South,” about the problems three generations of his family faced during their time in some of the country’s most racist periods.

Ralph eventually left the Virginia Quarterly Review and spent some time freelancing for the likes of the Wall Street Journal, but soon found his much of time spoken for again when he was asked to take be the Eudora Welty Visiting Scholar in Southern Studies at Millsaps College.

He held a course on the importance of photography and how it was an inspiration for Welty’s stories, and another on whether the writer must be a crusader — for example, should the writer be an impartial voice, or should they use their talents to crusade for a particular agenda.

Although the Millsaps College teaching gig is over, Ralph told me that he was preparing to teach a course on the business of publishing at George Washington University in January, and has a week-long residency at four schools in Alabama coming up in March. The teaching, combined with the writing and research for his third book proposal, is more than enough to keep him occupied — to his wife’s delight, he said with a laugh.

I asked him where he’d met his wife, but before he could answer our entrees arrived.

We had ordered the same thing: Bacon-wrapped pork loin served with corn maque choux, rapini, and sweet potato crackling. Every part of this dish was fantastic, if a little heavy. The bacon was crisp, the pork perfectly cooked, working well with the corn and potato.

Although the conversation got quieter as we both demolished our entrees, I was still able to learn about how Ralph met the future Mrs. Eubanks, with whom he has three children. They met at a church on Capitol Hill in the District. “I dated her roommate first,” he chuckled. They’re been married 28 years, and their three children are all pursuing careers in the arts.

I wondered whether, all these years after the civil rights movement, the Eubanks children had suffered from any of the racism that had been so constant in Ralph’s childhood.

“They’re multi-racial kids and they knew when they were younger that they looked different from other kids, but yes, growing up in DC, they were victims of racism,” he said. “Nobody ever called them names, but there was exclusion — something this election has really brought out.”

It was inescapable to separate our dinner conversation about Ralph’s extensive research and writing career from the aftershock of the election and racist vitriol seen on so many television news pieces and in newspaper articles covering Trump rallies and other events.

Ralph said that he had been to a Trump rally and that “some of these people wouldn’t think of themselves as racist, but they are associating themselves with that.”

He went to the rally with a white friend as part of his research for a piece he wanted to do for the New Yorker on returning to Mississippi after several years. “I was very much taken by the silence and the quiet when Trump spoke, it was like being in church. It was scary,” he said. Ralph had cut his hair short and wore a hat so that people wouldn’t easily be able to tell he was black, he said.

But the disguise wasn’t foolproof. “People have ways of seeing racially, knowing something is different. This older man asks me and my friend, ‘Y’all planning to vote for Trump?’ So I put on this Mississippi drawl and said, ‘I don’t think I’ve made up mah mind,’ and he starts yelling at us. I told my friend to keep walking,” Ralph said. “My friend was supposed to be my beard” and protect him against racist encounters like that, he added with a laugh and a shake of his head.

“What I saw at the rally — I knew that was the direction that things were heading at least for Mississippi, but I was wasn’t sure about the rest of country,” Ralph said.

Of course, that country elected Trump in November, something that doesn’t strike Ralph as a good signal for race relations. “I think at lot of people would say we’re at a point where there’s racism without people being racist,” he said. “There are the effects of racism, but then you have people who don’t want to admit they’re being racist with their actions or saying they’re racist.”

He added, “This last election, there was a lot of people saying, ‘No, this isn’t racist and you can’t pin the R word on someone,’ but if you start to deconstruct what is happening, at any other time it would be considered racist.”

On that thought we started to bring dinner to a close, finished with us splitting a fairly bland Key Lime pie. It wasn’t bad, just not outstanding — and that’s a compliment to the rest of the dinner having been so delicious.

After two highly enjoyable and educating hours, it was time for Ralph and me to make our separate ways home. On the way out the door, Ralph said he hoped I had a great Christmas back in England, and then we both wished each other all the best for the new year.

For all the direct and indirect discrimination Ralph has faced, it’s a testament to the strength of his character that he is one of the kindest, most thoughtful and intellectual strangers I’ve taken out of dinner.

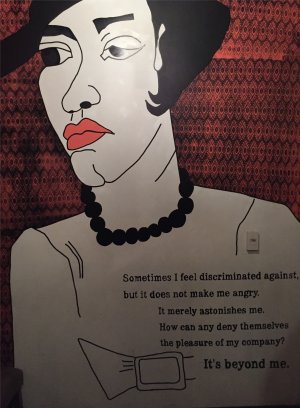

As we walked out together, I stopped to take a picture of a large portrait of Hurston painted in the entrance. I read the quote underneath, then looked to Ralph walking outside, then back at the quote. I smiled as I read it, because it sums up how I felt after being granted the honor of having even just a little time with Ralph:

Sometimes I feel discriminated against,

but it does not make me angry.

It merely astonishes me.

How can any deny themselves

the pleasure of my company?

It’s beyond me.

auxmlq

l0gou4