NEW YORK CITY

September 25, 2019

STRANGER: Ryan O’Callaghan

LOCATION: The Smith, 1150 Broadway, New York City

THEME: A former NFL player shares his coming out story

“You don’t always want to die, like your whole day is not just ‘I wanna die,’” former NFL player Ryan O’Callaghan tells me about years of suffering suicidal thoughts. “There is a lot of very dark moments but you still find little things throughout the day that are positive and uplifting. Obviously if I had given up hope I would have just done it.”

He wanted to kill himself because he was hiding the secret that he was gay, which led to depression and a plan to do it when his time in the NFL came to an end. When he wasn’t on the field for the Kansas City Chiefs he was refurbishing a cabin in the woods; the place he called his “crypt” where he planned to use a gun as a final solution.

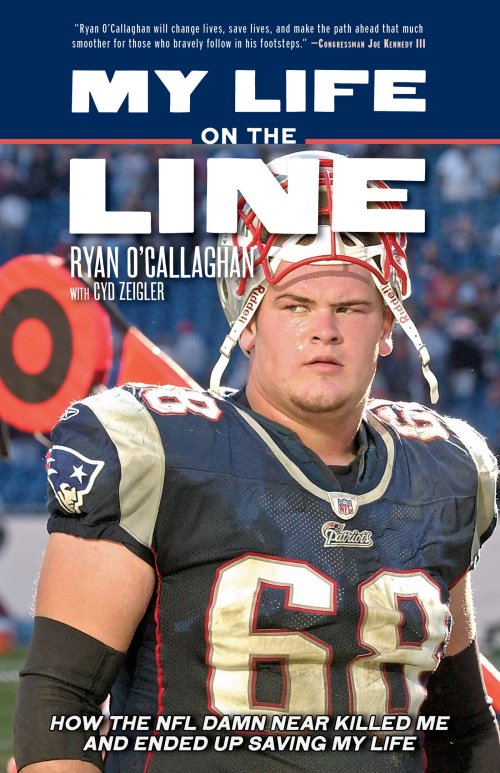

“Once my NFL career is over I’ll get in the truck, drive to the property, open this gun cabinet, and shoot myself in the head. . . . Nobody wants a fucking faggot around,” he writes in the opening chapter of his captivating book “My Life On The Line: “How the NFL Damn Near Killed Me and Ended Up Saving My Life.”

Ryan, 36, still has the imposing 6ft 6in thick build of a football player, and towers over me when we first meet at The Smith restaurant in Manhattan. Only when we sit down at our lunch table do we literally see eye-to-eye.

He talks in thoughtful, measured sentences and is a considerate dining companion, breaking the ice with chatter about the menu options. If he projects a slightly charming awkwardness, it’s only because doing an interview isn’t exactly how he’d like to spend his time. But he’s willing to do it to promote his book, as profits from sales go directly to a foundation he launched to help LGBTQ athletes with funding and mentoring. Although he identifies as an introvert, he’s doing book festivals, pride events, and more to hopefully help other people struggling with their sexuality.

“Before I was always hesitant to meet people and be in the spotlight because I didn’t know what questions were coming,” he says. In the book he talks about acting straight, developing an abrasive persona, and taking steps he thought might help mask his homosexuality — like waiting for an after-game shower until all the other team players were done, in case anyone thought he was trying to catch a peek.

He’s glad to have told his story in print, hoping it might help those in the closet, even if he’s not a huge fan of interviews. “I look at what comes from it, just helping other people and helping out my charity. If there was nothing at the end of, I wouldn’t be doing it. I’d be living in the country,” he says, then smiles, “which I still plan on doing.”

Being gay and wanting to hide his secret is what drove him to football in high school. AS he tells it in the book, he ditched his friend group of drama kids and took up the sport because “[i]f you were associated with the football team, you were straight. Period. No questions asked. Ever. So I decide I was going to play football.”

The decision put him on a career path that eventually led to the NFL. But the stress from his secret, coupled with pain from his injuries, drove him to his deep depression, alongside an over-use of weed and an addition to painkillers. In vivid terms in the book he describes smashing up opioids and snorting them just to get his day off on the right footing. It’s a brutally honest work with an incredibly sympathetic central figure. Over 231 pages he charts a story that begins with hearing gay jokes from family members in his childhood, feeling he had to act straight in college, and then firmly locking himself in a mental closet after the Patriots signed him as an offensive tackle.

About halfway through, he devotes several pages to recalling the specific details of the future day when he would kill himself; everything from the couch he’d do it on to the exact gun he planned on using. “I know how I’m going to die, and I know where I’m going to die. When? Is the only question. I get very close a couple nights to just saying fuck it and doing it,” he writes. When that would happen he’d call a close friend and reveal his suicidal thoughts, but never the reason behind them.

After Ryan quit painkillers and spoke to a therapist, he started the process of coming out, first to close friends and family in 2012. Then he decided that nobody should have to suffer the mental trauma that he went through, and worked with journalist Cyd Zeigler of sports-focused LGBTQ news outlet OutSports to share his story in a June 2017 article. Ryan asked for his email address to be included at the bottom of the piece, and says he was inundated with messages night and day from people in the closet asking advice — everyone from college kids through to pro athletes desperate for help.

Realizing that so many people suffered just as much as Ryan, he worked with the journalist to turn his story into “My Life on the Line,” in the hopes of offering solace to others and using the profits as a catalyst for his foundation.

“I genuinely thought I wouldn’t be accepted as an out gay man,” Ryan confides from across the table. But once he came out he mostly found plenty of acceptance among friends and family, although in the book he shares that communication ended with two people he had considered among his closest friends. “Every other friendship I had besides them I’m closer now than ever, just ‘cause they see how happy I am, and they’re just, I think, they see me happy and I’m honest with them, and I think that just brings us closer together” he adds, with such a nice smile I beam along with him.

“I was most conscious of how my family was portrayed in the book, so I was very careful to be kind and watch my language,” he says. Ryan writes honestly about his father drinking when he grew up, and tension it caused in the family, but says they have a vastly improve relationship now. “We’ve come a long way since then.”

His mother started, but stopped, reading the section of the book at the start when Ryan details his plan to kill himself, but other than that she has been supportive of his coming out. Because he came out to them first in 2012, he says, “this book is years later, so they pretty much know everything by now, so there weren’t too many surprise in the book. But that part, my mom reading my plan, that hit a little close to home.”

Early in the book Ryan talks about how at family gatherings some relatives would make tired old gay jokes (there’s one about a bar stool that many people have probably heard, and it’s in the book). These days he doesn’t hear those kind of jokes, but he’s so at ease with himself that he can laugh with his friends at certain things that would have sent the closeted Ryan into a tailspin. “I joke around with straight buddies with gay jokes, I’m not one to get offended by that anymore, just because I know where someone’s coming from. I think if people just ignored it and didn’t make comments it would be boring.” So when a friend nudges Ryan and jokes about a guy that they think he should pursue, he’ll jest with them. “I think it’s their way of trying to connect,” he tells me.

Ryan’s book takes on an optimistic tone at the end once he quits pills and comes out, and he continues the story in person with his earnest desire to help others.

He launched The Ryan O’Callaghan Foundation which, hopefully next year, will start handing out scholarships and support to LGBTQ athletes. “It doesn’t matter what sport, I think the statistic is something like 50 percent of LGBTQ [athletes] quit playing because of their sexuality and there ain’t no need for that,” he tells me. “I’ve had other guys, straight people, gay, lesbian, want to be mentors, so I plan on linking them up just to get ’em going. I think it’s more beneficial to give someone money and give them help along the way, not just say, ‘Here’s 10 grand, good luck.’”

The scope of the foundation’s success will hinge on the success of the book, because Ryan is feeding all profits to his charity. Much of his work until now has been on navigating complicated IRS forms and creating the website so that it could launch around the time of his book’s release. Next year he’ll shift to the stage of taking applications and possibly linking up with larger LGBTQ groups.

He welcomes work the NFL is doing to publicly support the community, including hosting groups for events and taking part in pride parades. “They have to be careful with what they do because not every owner is liberal and not all the fans are allies.”

But generally he describes the atmosphere within NFL teams as professionals; sure there might be plenty of talk among players about women they’re getting with, but Ryan never heard people throwing around vicious homophobic slurs. And that makes sense, he says, because the NFL is a professional organization, he tells me to think of it like any other workplace. “You coworkers can’t be saying ‘faggot’ in the office.”

Part of the promotional work for the book means doing interviews like lunch me at The Smith, and giving talks like one later tonight in the city. Last week he was in Boston for a book signing and future plans include trips to Miami, Minneapolis and Kansas City.

His football injuries — including a major shoulder injury and having five screws in one finger — still aggravate him daily, so he typically takes a week of rest in-between touring. “My body’s just like go, go, go and I don’t like doing that; I get sore.”

Ryan hasn’t touched “real” painkillers, the kind he was addicted to, in seven years but says he takes a lot of ibuprofen to help with the residual pain from his playing days. “I don’t have to be on my feet eight hours a day and dig ditches, so I can do a bunch of stuff and then if I’m sore, when I’m sore, there is no if, I just relax.”

Talk about injuries leads to discussing Colts quarterback Andrew Luck, who made headlines earlier this year retiring at 30 because of his injuries. “He’s a smart guy, he’s made a shitload of money, he knows his body better than anyone else, and nagging injuries can wear on you in a lot of ways,” Ryan says. “I don’t blame him, I think a lot of these guys that play 20 years are fucking crazy. I mean they must really love football or have a family that spends a lot of money or something. I played with guys who are like 40 years old and they’re still playing, and they’ve got their reading glasses on in the meeting room. Just go, retire.” He shrugs. “But some guys love it, and that’s great, and I’m sure if you’re passionate about it, it makes it easier.”

When Ryan was playing he was at least 330 pounds, but across from me looks healthy and fit, part of what he says is an ongoing weight loss effort. “I’m still trying to lose like 20 pounds, so I’ve been watching what I eat,” he confides.

As if on cue, our waiter delivers our lunch, with Ryan choosing the steak salad served with arugula, endive, goat cheese, tomato, and balsamic vinaigrette. Because of his lingering injuries he’s unable to work out, or even run a mile. So he watches what he eats, typically eating dinner at 5.30pm “like an old man” so it burns off before bed. Sometimes he’ll treat himself, and he tells me last night he splurged on a short rib and bone marrow pasta dish. “It was fucking rich but it was really well done, it was pricey but it was worth it. I enjoy a bougie meal sometimes.”

Coming out and finding a reason to live changed how he thinks about his body, Ryan says: “You go from not caring about your life and wanting to die, to enjoying life and wanting to live so, okay, I better do this, this and this.”

Although Ryan’s having salad, he promised not to judge me if I ordered something unhealthy. And so I start on the massive Burger Supreme: a patty of dry-aged short rib blend in a gruyère bun topped with raclette cheese, watercress, and red onion, served with a tangy green peppercorn sauce and a generous portion of fries. I praise the burger and tell Ryan I eat out fairly often as I don’t cook at home.

He laughs. “Really? Sometimes I just watch the Food Network and I’ll see something and I’ll go to the store and buy it, cook it, I enjoy cooking. But I feel pitiful sometimes because I can’t reach up in the oven with two arms because this arm doesn’t go up,” and he moves his left arm slightly. “So a lot of people look at me like, ‘Oh, he’s a big strong guy,’ but I can’t even reach all the way into an oven — but that’s my reality.”

Ryan rarely watches NFL games now; he’s generally not a follower of football and in his book he confesses to never having a major interest in the NFL nor watching games when not working. Instead, he’s a big lover of NASCAR and tells me he’s looking forward to catching a race in Kansas City. “I appreciate the NFL but I like NASCAR,” he says, having developed an interest in it watching races in Missouri when playing for the Kansas City Chiefs. “A lot of people say it’s just cars going in a circle, it is, but when you’re at the track it’s just immersive, it’s so loud and there’s so much going on. It’s amazing people watching.”

His home base is Redding, California, where his parents live. When he first left the NFL and came out he stayed with them a while, but has lived alone for five years. He’s dated guys in recent years and although he isn’t officially seeing anyone right now, Ryan says he’s talking to someone in South Carolina — and would move for love.

“I would live anywhere, I would move to Guam for five months to see if a relationship would work,” he says in a clearly earnest way. “I’m one of those old school guys that value connections with people over anything else. When I first came out I thought by 35 I’ll probably have met someone. When I hit 35 I was like, okay, maybe 40. It would be nice I guess, but being single I’ve learned a lot and grown a lot.”

If he’s out on the town he doesn’t tend to frequent gay bars, saying they’re no longer making the connections he values. Instead, he’s a huge fan of dive bars. When he travels to certain places he’ll research the best dive bar, and that’s how he wound up what he describes as a “historic shithole” on a recent visit to Des Moines, Iowa.

And if you see Ryan at a bar, consider treating him to his favorite drink. “Extra dirty Ketel One martini, up, no vermouth, blue cheese olives if they have them. I get it as dirty as a toilet, so everyone is like ‘ugh, it tastes like saltwater,” and he laughs.

He nods. “Nothing compared to that first week after originally came out, and I get more emails on the foundation’s email now, but I still have people reach out. A lot of stuff about the book, people reading it. I think the most recent email was from some guy who bought the book and then he started reading it, and realized it was about a gay guy. He wasn’t gay and he said he almost stopped reading it, but he kept reading it any he was happy that he did,” says Ryan, eager to reach straight people as well as LGBTQ folk.

Beyond working on the foundation and promoting the book, Ryan says he’s not sure what the rest of 2019 and the new year have in store for him. And he’s perfectly all right with that.

“I don’t worry about it,” he tells with me a smile. “I’m the type of guy that can literally do nothing and I’m not bored. It’s rare that I do nothing but I really don’t worry about. I figure I’ll meet someone at some point. I used to worry so much about so much shit. But now, I’m just like: Am I happy? Yes? Okay, then that’s fine.”

3ogwq1

0gv78k