SILVER SPRING, MARYLAND

April 24, 2025

STRANGER: Doudgy “Dew” Charmant

LOCATION: Gisele’s Creole Cuisine, 2407 Price Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland

THEME: An artist describes the evolution of his work focusing on the human experience

What started with Doudgy Charmant scribbling on the walls of his childhood home in Haiti developed into a flourishing career as an artist who’s thriving in Washington, D.C.

Doudgy, 26, never stops creating. Ahead of our dinner interview, we’re meeting at his studio in the Westfield Wheaton mall in Maryland. When I arrive, he’s got a paint brush in hand as he works on a Bruce Lee painting, commissioned by a collector who does martial arts.

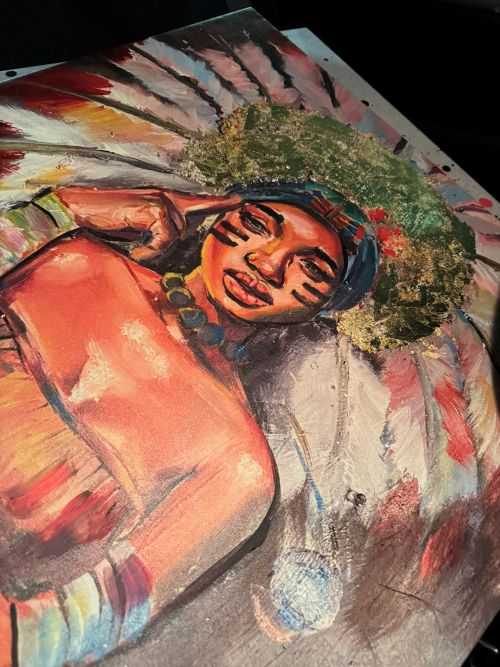

Although still in its early stages – it will take him up to eight days to complete – the canvas already shows off some of Doudgy’s signature style. Vibrant, warm colors of acrylics and oils, human expressions that have startling depth, drawing the viewer in and keeping them engaged. His work consistently tells stories that can change with each look at a painting.

His deft touch has not only created a diverse and ever-growing roster of regular commissions from collectors, but also notable works with major parts of D.C. life. Most recently, he worked with the Giant supermarket chain to design an eye-catching reusable tote bag as an initiative to preserve the planet by reducing plastic usage for them. It follows an earlier project where he painted a mural on the side of a Giant location in the city.

Over the years, Doudgy has also scooped up awards and extensive recognition for his creative output. Highlights include a Pentagon residency for his art, along with being profiled in a Capital Emmy award-winning short documentary video about his work titled “Black Artist living in Montgomery County: Doudgy Charmant.

Eager to learn more about his life story, I’m ready with my list of questions for dinner. As he packs up his gear before we decide on a place to eat, the around-the-clock work he puts in is made clear by the splatters of paint all over the bags he uses for transporting it.

“Have you ever had Haitian food?,” he asks. I shake my head.

That’s how we end up a few minutes later at Gisele’s Creole Cuisine, close to the mall. Doudgy speaks highly of the food, the venue and owners. And as we take our seats, he also points out that there are some pieces of his art hanging from the walls.

As we discuss the paintings, he says, “Of course, the colors and the vibrancy pull you in, in a story that connects you to the frequency of God, allows you to witness love, feeling the visual. Art is to a certain extent propaganda. The person sees it and has their emotional reactions. And that’s very spiritual. I can’t help the effect it has on somebody. However, I do my best to maneuver that energy so that it is as pure as possible.”

Also known as “Dew the Artist,” Doudgy has lived in the District for many years, after a journey that took him from Haiti to the southern U.S. and finally his current home.

“My first experience as an artist was scribbling on the walls with crayons and ink marker pens, and my grandma and mom used to be so upset,” he says with a laugh.

“But my great grandma Misilia did encourage me to keep painting, to keep doing art,” he adds, noting that she gave him some scroll to paint or draw on any time he got the urge.

What started out as scribbles moved on to trying to draw people, and in particular he recalls around the age of six tracing a picture of the rapper 50 Cent. Then his uncle Edwuine Charmant, a professional artist, saw the work. “He got so upset because I was tracing. He was a very prominent artist in Haiti, he had done a painting for the Haitian president, so for him to see his nephew tracing, it was like a disgrace. So he said he would teach me,” Doudgy says.

That’s how he started to develop and refine his natural artistic talent, starting with the structure of drawing a face, such as where the lines of eyes should go to look natural, and so on. Fascinated with art from an early age, Doudgy would then learn as much as he could from different artists and styles, taking things he liked to the uncle to find out more about the varying techniques, paints and more. “Wherever I was at, he would help polish it,” he says.

“I went wherever my spirit was leading me, he just made sure that I was going there in the best way possible,” Doudgy adds. “So when I picked up acrylics, he made sure I was blending it properly, that I was mixing it well. I was applying the different lighting and contrasting techniques to make it look as best as possible. That’s how he guided me.”

Doudgy’s dad Ralph Bricene Charles was also a prominent artist in their home country, but Doudgy grew up thinking the man was dead. It wasn’t until he was around 15 years old that his father called him from New York and said that he wanted to meet his son.

“I was just overfilled with joy, that wow, you’re alive. And he said he was calling to apologize. And I was like, come on, man, we’re past that. I’m just glad you’re here,” he says.

They ended up meeting when he turned 18. Their first meeting was in New York, when Doudgy was visiting his brother. Unbeknownst to Doudgy, his grandmother had arranged for Ralph to show up at where his son was staying. “And he walked in the room and I looked at him and he’s like, ‘That’s my son.’ Then he asked me, ‘What’s up, man?’ Wow. It was cool, we hugged it out,” Doudgy says.

“It was beautiful, man, because you know, a father in a kid’s life means so much. His presence, me seeing him for the first time, it just shifted my life completely. It was just, I can’t even, I don’t have words to connect to that,” he says.

Which perhaps explains why Doudgy’s artwork is the perfect vehicle for expressing what he struggles to put into words. That’s how he can tell his story and make his connections.

His father has since passed, but his influence clearly lives on – including a short film Doudgy made that expresses his dad’s legacy. It focuses on a sketchbook of drawings by his father, and Doudgy’s work to take the sketches and turn them into his own paintings.

He has also presented his father’s artwork at the offices of the Maryland Comptroller, Inter-American Museum, and he speaks with affection whenever discussing Ralph and the impact on his work.

We pause as the food arrives, and Doudgy walks me through it (he ordered for us). For a starter, we’re splitting a pâté kòde – a patty filled with herring and cabbage. Flavorful, fresh and perfectly cooked, it’s an excellent first foray for me into Haitian food.

And for the entrees, we’re both having a vegetable stew called diri sospwa legume, although mine comes with goat. The aromas are incredibly enticing when our friendly waitress sets our plates down. Doudgy shows me the right way to pour the stew accompanying black beans over rice, and then we eat.

Dining on this great Haitian food naturally brings the conversation back to that country, and how Doudgy ended up leaving. Tumult there meant his family eventually moved to the U.S., first to Miami, then Atlanta and then finally settling in the District.

By then, Doudgy was fixed on pursuing a career and a life as an artist. And it’s in the city where he first started hustling to sell his works, which he recalls as a terrifying prospect. He was only 18 years old at the time, and one day he just decided to take some of his paintings and arrange them on 7th Street NW outside of the Capital One Arena, where other artists were selling their work. “It was scary, I was nervous, I didn’t know what was going to happen there, it was all so unknown.”

He soon started talking with the other vendors, as well as performers like a drummer, and quickly found a community to sit with. Doudgy put prices on his art, and while waiting for potential customers he would work on a small canvas. It didn’t take too many times being at the location before he started to draw crowds numbering in the dozens watching him work.

One day, a man named Jordan Kilson approached Doudgy to ask if he would be interested in teaching children art at the National Center for Children and Families. He jumped at the chance. “Because I lacked a father figure in my life, I wanted to be there for these kids as a big brother,” he says.

This work went on for three years, but he still maintains a close connection to the organization – some proceeds from the Giant bag sales will go to it. He adds, “I’m very grateful for that. I wanted to build something, and now I get to support something, and push it forward.”

Through this work, his regular sales and painting outside, and just making connections in D.C., Doudgy’s artistic career flourished, to the point where he’s living his dream of creating full-time. That includes expanding his world to clothing and other potential avenues.

I mention how in his Capital Emmy award-winning documentary, Doudgy expressed that his creations center around the themes of love, joy, sadness and revenge. After spending time with Doudgy, and seeing his positive-focused art, I tell him that I can’t see him as a vengeful person.

“The best revenge is self love and self elevation,” he explains. “So, best way to get back at someone is to not get back at them – it is to let go, to release, of people and emotions.”

And that optimistic, positive-minded mentality is a through-line of not only his work but also how he tries to live. “There’s days when the sun don’t shine as bright, and that’s okay. There are days when I may not feel like helping somebody or I may get emotional and angry upset, and then do something that does not align with the frequency of God. However, if the sun had one cloudy day, two cloudy days, it is a known fact that it will be sunny again within the sequence, and it will keep being sunny again,” he says.

As he continues his creative endeavors, Doudgy stresses that he strives to remain “decent” in what he does. That makes me ask him what makes a person decent.

“What makes a tree a tree is the fact that it vibrates at that frequency consistently day in and day out without stopping. What makes a sun a sun is the fact that it does what the sun does every single day without missing a beat. To be a decent man, you’ve got to be a decent man every single day without missing a beat,” he says.

“To remain decent, you’ve got to return to that state of being. You’ve got to vibrate at that frequency. To be a decent man is to feel like God is pleased with my work. And there are some days I feel like that. Some days I don’t feel like that,” he explains. “But right now, I do feel like that. And so the goal is to just keep going.”