NEW YORK CITY

November 11, 2025

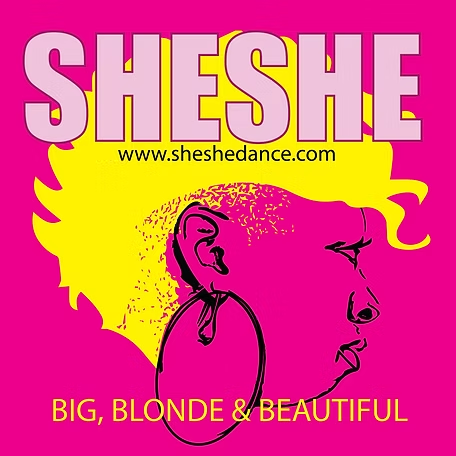

STRANGER: Azusa Sheshe Dance

LOCATION: Trattoria Trecolori, 254 West 47th Street, New York City

THEME: A self-taught singer charts her own path in the theater and subway

Whatever Azusa Sheshe Dance wants, Azusa gets.

A starring role in the stage musical “Hairspray?” Done.

A coveted New York-sanctioned singing spot in the subway? No problem.

Over 50,000 followers on TikTok and growing? Of course.

It’s all intentional, not dumb luck. Call it activated luck. When Azusa fixes her attention on a goal, she works hard to get it. That’s how the Tennessee native went from a casual singer to self-directed performer, riding her natural vocal talent northeast to the Big Apple. She’s cemented herself as a New York fixture; it’s hard to imagine the city without her now.

That’s not to say her path here was without moments of self-doubt, as I’ll learn over a laugh-filled, warm lunch with her on a frigid day in Manhattan.

Azusa, in her fifties, appears in a riot of pink – from her hair to her clothes to her boots – with an outgoing personality. But don’t mistake flash for superficiality. She’s a level-headed, hardworking artist who chooses her stages and energy deliberately.

One of those stages is the New York subway. In 2016, soon after moving to the city, Azusa auditioned for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Music Under New York program that gives select performers dedicated spaces at train stops to sing (and take donations).

At stations like 14th Street (one of her favorites), Columbus Circle and Times Square, you might get lucky and be there the same time she’s performing. You may be so taken in by pausing to hear that powerful, gorgeous voice singing hits like Ray Charles’ “Night and Day” or The Shirelles’ “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” that you miss your train.

“The subway is my heart,” she tells me. “I’m just trying to spread some joy and happiness on your commute, because it’s hot as hell, it’s cold as hell, you’re broke as hell, you’re tired as hell, you ain’t got no money, the train is delayed, the train passed you, it’s a lot going on.”

She adds, “And it could be one song that jogs a memory for you, that’s the song I went to the prom on, man, that’s what me and my granny used to sing all the time, that’s all I knew. As long as it puts a smile on your face, that’s what it’s about. It’s about finding us some joy and happiness. I’d rather do that than make a million bucks. But I’ve still got to pay rent.”

Then she laughs, a contagious chuckle that has me laughing just as hard with her.

And rent gets paid. Before the coronavirus pandemic threw everyone’s life into chaos, she was pulling in anywhere from $500 to $1,500 within a few hours. Things aren’t as lucrative since the pandemic, but still good enough to persist with the work. TikTok, which allows gifts that equate to monetary donations, helps, as do other performing gigs.

Her schedule depends on what’s going on each week, whether that’s auditions, other theater-based work (like selling merchandise at the Broadway hit “Hamilton”), or anything else.

Today is not a subway performing one, so Azusa has time for our interview. We’re dining in midtown at Trattoria Trecolori. I’m there on the early side, so have a vantage point from which to see Azusa sweep into the restaurant soon after, the other diners’ heads turning as this tall pink cloud glides in. Friendly from the first moment, we’re soon diving into her life story.

Azusa is such a compelling storyteller that the fact we’re eating is almost an afterthought. That’s no slight to the restaurant, which brings her a generous plate of fettuccine alfredo.

I’ve gone for a sandwich of breaded chicken cutlet, topped with marinara and mozzarella on a crispy baguette — rich, well-cooked, and just the right portion. Then it’s back to Azusa.

She was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, as Azusa Quinitta Dance.

Even her name is another testament to the agency with which she controls her life. It’s pronounced “Ash-you-uh,” not “Az-oo-za.” She recalls being bullied about the name as a kid, so it’s triggering when it keeps happening. She won’t respond when strangers keep mangling her first name. You’ll get grace the first instance, but silence after that.

“Because my parents taught me a long time ago, if somebody wants your attention, they’re going to call you by your name. And I said, that ain’t my name, so I’m not answering. But I had to remember now I’m in this entertainment thing, I have to say, ‘Oh, that’s not my name. You can keep addressing me as such, but I’m not going to answer,’” she adds.

As for Sheshe, that’s an affectionate name Azusa’s two kids gave her. “They said it’s fun, it’s catchy and nobody goes by it – and it’s one word, like Cher or Pink. And my kids have created me and trained me. They were my original management team and they still are to this day. They were the ones that said you need to go to New York.”

She has a son, who’s a choral singer, and a daughter who dances. When they were growing up, their mother would drive them to and from gigs at the Chattanooga Theater Center. Azusa had dabbled in the world of the theater, with a few tentative auditions and roles, but had no plans for performing as a full-time gig.

She was used to singing in church as a child, but the idea of doing so professionally never crossed her mind. Then one night, she let her kids pick a movie to watch, and they chose “Hairspray,” the musical of John Waters’ story about Baltimore, dance, racism and more, all set in the 1960s. “At first, I thought I didn’t want to see it. ‘Hairspray?’ What a stupid name. But I absolutely loved the movie, and I love me some Queen Latifah.”

In the movie, Queen Latifah plays Motormouth Maybelle, who sings the soulful gospel-style number “I Know Where I’ve Been” – a song Azusa instantly adored.

Then one day in 2011, her children came home to say that the Chattanooga Theater Center was planning to stage “Hairspray” and that auditions were open. “I told them, ‘That’s good, I can’t wait for y’all to audition.’ And they said, ‘No, no, no, no, we need you to audition.’”

Knowing from church and home that their mother was a great singer, they urged her to try out as Motormouth Maybelle. “I was like, I don’t think so,” Azusa confides. She couldn’t read music, instead learning singing by watching and hearing others perform. Still, she didn’t want to disappoint her children and so she went to the audition.

“Hairspray” was such a hit movie that the auditions went till two in the morning. Some people went dressed as the characters they wanted to play, Azusa just went as herself. “If I got the part I wanted them to choose me for me, not because of anything extra I did.”

She finally sang, got home, and waited. And waited. Then a couple of weeks later she got a message asking if she was still interested in the part. “I thought either they have the wrong person or they were messing with my feelings, because you didn’t want me and now you do?”

The team behind the show nevertheless convinced Azusa to at least see the full script and attend a rehearsal. “When I walk in to the theater, it’s all these actors doing their la-la-la-las and doing vocal runs and raspberries. I said, I do not belong here, they’re doing way too much and it is not familiar to me,” she shares. “So I had already decided, I’m out.”

But she made a promise to herself to stay until at least the first break, because ducking out early would have sent a bad example to her children. The break arrived, she got ready to leave, and then the director came up to her with a request. He asked if she could take “I Know Where I’ve Been” home, practice it, and come back the next to try it.

“It’s funny how God and the world works in mysterious ways,” she says. “My kids really wanted this for me, and I really wanted this – I was being scared. So I went home and worked on the song, the kids helped me all night long and they were so excited.”

The next day, nervous but determined, she took to the stage to sing in front of the full cast and crew. She didn’t look at them, instead calming her nerves by focusing on the director sitting at the piano. He started playing, asking Azusa to sing a few bars. Those few bars ended up being the entire song. When she finished, she got a round of vigorous applause from everyone in the room, several people with tears in their eyes, and the director excitedly slammed on the piano keys, shouting, “This is gonna be a goddamn good show, I can’t wait!”

“And I thought, oh! Maybe I can sing,” Azusa says with another laugh.

Turns out, the stage was exactly where she belonged.

She fondly recalls what she describes as the fun of working the sell-out run of “Hairspray,” with her turn getting so much attention and praise it got to the point audiences started applauding the second she got on stage, before she even said or sang a word.

“When I saw the show from the wings, that’s when it kind of clicked that I’m a part of this, I fit in,” she tells me. “One of my friends said, ‘You walk out on the stage and people lose their minds. I’ve been doing theater for 10 years and I’m still trying to get there. You’re a natural.’”

This kicked off a productive few years performing in various roles at the Chattanooga Theater Center. One she’s particularly proud of was in 2014 in Nella in “Gee’s Bend,” a play about quilt makers in the all-Black, once-enslaved, population of a small Alabama town.

“Nella was an older lady reminiscing about when they were sharecroppers and the white man was coming to take their stuff because they couldn’t afford to keep it, and there was this baby pig she had fallen in love with,” says Azusa. “I had to do this whole monologue, I was terrified. But I channeled my granny, she grew up in Murfreesboro out in the country, on a farm with an outhouse, running around with the chickens and milking cows. So I was channeling the stories she had told me into my character. And it was just phenomenal.”

By that time, person after person kept telling her she had to take her skills the next stage. And that meant moving to New York.

She was initially dubious about a move, with children still in school in Chattanooga. But then a number of events converged at the same time – she was out of work because her then-place of employment closed her department. Her kids graduated. Her grandma passed away. “I felt like I was living a sad country song,” she says, chuckling. “Yeah, it was time to go.”

Before heading to New York in 2016, she gave herself a five-year goal: get an agent, get a manager, perform on the stage at Harlem’s famous Apollo Theater. Five years or bust.

“I accomplished it in three months.”

Hustling non-stop, she took part in an amateur soul night at the Apollo, placing third.

She also booked a paying gig for the 13th Street Repertory theater in the role of Enez and in the ensemble in “Yaki Yim Bamboo,” a children’s musical. This show let her develop the art of Bunraku, a type of Japanese puppetry. “The audition said only Caribbean-authentic accents need to apply. I’m a Black girl from Tennessee, don’t tell me what to do,” she says, smiling.

At the audition, she had to sing a song “Shake Me Coconuts.” Cracking up at our table over the memory, she says, “I ain’t never been overseas to no island, but there was a guy I dated from the Bahamas. I could never understand what he was saying.” So she called him, listening to his accent, and used that to knock the song out of the park.

I’m honored that she does a mini recreation at our table, swaying slightly side to side, singing:

Shake me coconuts a-boom-boom

I said me shake me coconuts a-boom-boom

Watch out man, the fruit from the coconut tree

I said me shake me coconuts a-boom-boom.

When I transcribe the audio of our interview later, I’ll play it on repeat just to smile.

By the time she was waiting for her train home, she had a message giving her the part.

“So I tell people all the time, just show up, never tell yourself no, because you never know. People see the same old all the time. But when you show up for a part that they never thought about, who knows, you could get it because they want to go a different direction,” she says.

The agent and manager quickly followed. Charting her own path, Azusa used her determination and inherent talent to earn each role she sought.

That includes the MTA’s Music Under New York program that she found out about early during her time in the city, auditioning and winning her spot in 2016 – a smash year.

“I thought people were singing in the subway to get a dollar, I had no idea it was a program. My aunt told me about it, she thought it fit me,” she says. “I was so excited because it gives you an authorized spot and once you’re in, you’re in for life, and they put you at elite stations.”

It’s still a good financial gig but was more lucrative before the coronavirus. Once the pandemic hit, there weren’t many commuters for a long time. Even when people started returning to the subway, they had changed. “People have just gotten even more selfish and cold-hearted. It was a very different world before,” she says – but adds there’s still enough joy to persist.

Her playlist is whatever she feels like, and she won’t think to perform as another artist or chance a song she knows is beyond her range. “I have freedom, it’s my jurisdiction.”

She also loves people watching, as well as many of the interactions with fans and other well-wishers, including children, who sometimes like to try singing along with her.

There are challenges, including the heat in the underground stations, particularly during the scorching summers. But being from the South, she’s used to coping with heat.

Another problem is the occasional thief hoping to grab donations from Azusa’s bucket. But having already endured a robbery at the bank back in Chattanooga where she once worked as a teller, she’s not about to let a subway robbery happen. She recalls grabbing the hand of one would-be thief, telling them, “Let this be your blessing that I’m not gonna kick your ass.”

If you’re in the subway and see Azusa singing, another way to avoid getting on her bad side is to never ask her to sing “New York, New York.”

She rolls her eyes. “Do you know how many artists in New York are singing that? I’m not a cookie cutter. I’m not doing anything everybody else is doing. People ask me, ‘How did you get this? How did you get that?’ By being me. That’s part of y’all’s problem. You’re always trying to be somebody else.” She adds, “Don’t nobody want you in a costume looking like somebody else. They want to see the real you, that’s what sells.”

And it’s also what helped her quickly gain tens of thousands of followers on TikTok, where you can still see her live-streaming from the subway whenever she’s performing.

Her signature pink style is part of that unique persona, and even at home she’s got pink towels, bathrobes, washcloths and more. “Everywhere I go, I know I attract attention because I deserve attention, and I should dress as such. That was one of the things that got me through Covid. Every day I was getting up, thinking am I supposed to be here? Do I go? Am I gonna die? So I would dress like I was going to a show because that’s what was getting me through.”

And that’s how she transformed her closet into what she calls “performance wear,” mostly pink, because it stands out among the grays and the blacks of the city. “Baby, if I’m wearing pink, if you don’t know my name, you’re gonna know me by my look. And you’re going to see me everywhere, on a rainy, dreary day you can still see me 10 miles away.”

You’ll be able to see her in New York for many years to come, pursuing whatever goal she feels a pull toward, no matter what shape the stage might take.

That might include more performances of “Houn’ Dawg,” a play she wrote about the life of blues artist Big Mama Thornton. A friend told Azusa she reminded them of Thornton, and Azusa went deep, learning her story, then writing, acting, and singing it. “I’m always trying to push myself and challenge myself to do something new,” she tells me.

Our waiter returns to take our empty plates. As we get ready to wrap up the interview, I ask Azusa whether the gregarious person I met is the same behind closed doors, like back home in her pink palace sanctuary.

Does she ever need quiet, alone time? She thinks for a second. “I do at times. And it’s funny, one of my favorite phrases, it’s from “Dirty Dancing,” when they say, ‘Nobody puts Baby in the corner.’ I like that phrase, but I have my own way. Nobody puts Baby in the corner – but if Baby is in the corner by herself, leave her the fuck alone.”

“I’m never gonna change being me because that’s what’s been working for me,” she says. “Life is very simple. People make it hard. If you just stick to the basics, you can live a great life.”

Excellent article on SheShe! The title is so correct… Nobody Puts SheShe in the Corner. I love the presentation of her and really enjoyed the video clips. I wasn’t familiar with Dining With Strangers before, but I am now and so will be following you. Btw, her middle name is Quinitta. I am the auntie.

Thank you for the kind words! And I fixed the middle name mention.

Anthony, I can’t thank you enough for this incredible article. It was an honor to sit and speak with you. I so appreciate you seeking me out for the true story and sharing more JOY. You’re a phenomenal detailed artist and hope this article helps others see you SHINE as well. I’m so excited to share your article with everyone. HAPPIEST NEW YEAR wishes to You. ~SHESHE

Happy new year to you too! It was one of my favorite dinners in 2025. You’re an amazing person, fantastic company and I will make a point to say hi next time I’m there and you’re performing.

Azusa is an enigma wrapped in pink! Her energy, style and talent are unique. She’s absolutely one-of-a-kind and we are honored to have her. I’m her manager and I am so proud of her and all she has accomplished. She’s a determined self-starter who puts her action into whatever she attempts. We’re honored to share the journey with her. Continued success!! This is a great article and I love the pix and videos!